What Do The Data Say?

In 2019 Andrea Jones-Rooy, a data scientist at NYU, reported her response when she is asked a routine question: “What do the data say?”:

“Data can’t say anything about an issue any more than a hammer can build a house or almond meal can make a macaron. Data [are] a necessary ingredient in discovery, but you need a human to select it, shape it, and then turn it into an insight….”

Following Jones-Rooy advice, what can we say about this graph of mortality data?

Context: Deaths of Despair

In 2015 Princeton researchers Anne Case and Angus Denton documented an increase in all-cause mortality of middle-aged White non-Hispanic men and women in the United States between 2009 and 2013. Extending their paper, they published a 2020 book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Deaths of despair are dominated by deaths caused by suicide, overdoses, and alcoholic liver disease.

Figure 1 from their 2015 paper shows the mortality line for U.S. Whites ages 45-54 increases while all the other series decrease over the 23 years in the study period. This striking pattern sets up Case and Dent’s analysis of possible social and economic causes for White deaths of despair.

Who is included in the data?

Last week, Joseph Friedman, Helena Hansen, and Joseph P. Gone added to the ‘deaths of despair’ discussion in “Deaths of Despair and Indigenous data genocide”, The Lancet, available here.

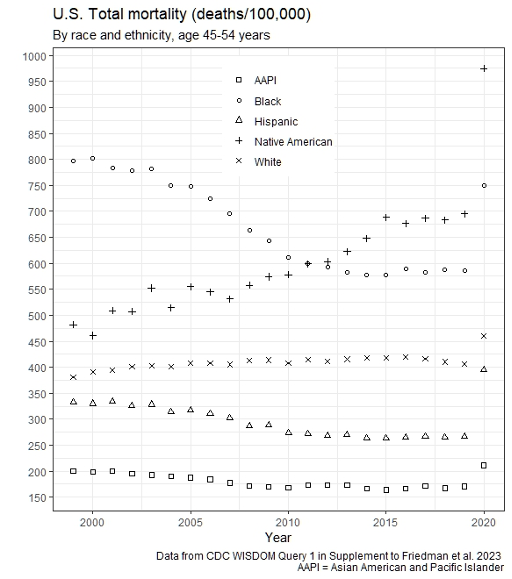

Using U.S. CDC Mortality data in the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020 table, the authors show crude mortality rates from 1999 to 2020 for five demographic groups. A version of their graph appears at the top of this post.

The graph shows that Native Americans ages 45-54 experienced dramatically increasing mortality relative to the other groups over the 21 years span in the data. While Black mortality decreased over the 21 years, it remained 50% above the mortality for White people from 2010 to 2020. All groups also show a 2020 increase in mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The authors disaggregated all-cause mortality and investigated deaths caused by overdose, suicide and alcoholic liver disease as deaths of despair. They summarize their analysis:

“…Native American communities have had substantially higher midlife mortality, and mortality from deaths of despair, across all years of available data. These inequities have worsened considerably over time. Nevertheless, the narrative of overdose, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease as White American problems— tied to economic disinvestment from working class White areas and related loss of social status—has reached widespread prominence as an explanatory framework in academic and popular press literature. Yet this core idea of the uniqueness of White people being at greater risk to these causes of death, was only made possible by the erasure of data describing Native American mortality.”

Who is included in the data conversation?

Friedman, Hansen and Gone offer two recommendations to prevent exclusionary data practices.

1. “…Native American people should be specifically enumerated and not categorised or labelled as other. “

In many communities, the number of Native American people may be small. The authors suggest specific analysis and presentation methods to deal with the technical issue of small counts in stratified tables.

2. “…in the context of a long history of disrespectful, irrelevant, and exploitative research among Native American communities, it is essential that Native American concerns are centred in collection, maintenance, and sharing of community data… Researchers should prioritise gaining the trust of Native American communities, ideally through Native-led research endeavours and consultation processes.”

Why stratify health data by race and ethnicity?

Why collect and stratify health data by race, ethnicity, and other demographic factors?

Friedman, Hansen and Gone remind us of the appropriate aim:

“Although the description of heath inequalities is a necessary part of work towards their amelioration, substantial efforts should be taken to ensure that the primary results of such findings are tangible efforts to improve them, rather than stigma.”

Acknowledgements

Thank you to The Lancet, Friedman, Hansen and Gone, and the CDC. I am very glad that journals, authors, and institutions embrace the elements of reproducible research. The CDC WONDER database system enables users to save queries. Friedman, Hansen and Gone provided the links to their data queries in the article’s Supplementary Materials and described the steps taken to produce their tables and graphs. I used their first query to produce my version of their data plot, using R statistical software and the ggplot2 package.

Thank you to Neil Lewis. I found Jones-Rooy’s paper cited in an article by Neil Lewis, a behavioral scientist at Cornell University. Lewis studies the equity implications of social interventions and policies. Lewis’s article presents a “both/and” discussion of standardized college admissions tests in the January 2023 issue of The Atlantic, “Are Standardized Tests Racist, or Are They Anti-racist? Yes.”

Lewis wrote:

“These two perspectives—that standardized tests are a driver of inequality, and that they are a great tool to ameliorate it—are often pitted against each other in contemporary discourse. But in my view, they are not oppositional positions. Both of these things can be true at the same time: Tests can be biased against marginalized students and they can be used to help those students succeed. We often forget an important lesson about standardized tests: They, or at least their outputs, take the form of data; and data can be interpreted—and acted upon—in multiple ways.”

All links accessed on 1 February 2023.