A3 Problem-Solving and the Model for Improvement

Some organizations choose to use A3 forms and structure to document problem-solving and plans. In a recent project, I’ve looked at how to combine the Model for Improvement with an A3 form to gain the strengths of both perspectives.

Similarities

I’ve argued that the Model for Improvement—three questions linked to Deming’s Plan-Do-Study-Act test cycle--is a general-purpose algorithm to achieve a goal. You can use it to solve problems in operations, where there is a gap between expected performance and current state. You can use it as well as for innovation projects, when you need to build a new or renovated system. If members of an organization have skill in posing and answering the three questions and also know how to test changes effectively, the organization has a strong foundation to improve performance.

Lean experts point out that A3 problem-solving is not rigid adherence to a specific format carried out in a strictly linear fashion. John Shook in his 2008 book, Managing to Learn: Using the A3 management process to solve problems, gain agreement, mentor and lead (Lean Enterprise Institute: Cambridge, MA) shows that effective A3s emerge from iterative discussions and revisions.

Shook clearly states that the precise structure and labels of boxes of an A3 form are flexible:

“It can’t be stressed enough that there’s no one fixed, correct template to use for an A3….The author decides what to emphasize depending on the specific situation and context. It is not the format of the report that matters, but the underlying thinking that leads the participants through a cycle of PDCA (plan, do, check, act).” (Managing to Learn, p. 10)

For Shook and other Lean experts, the point of A3-problem solving is not simply to solve an immediate problem but to develop problem-solving skill in individuals and organizations.

More on A3 problem-solving

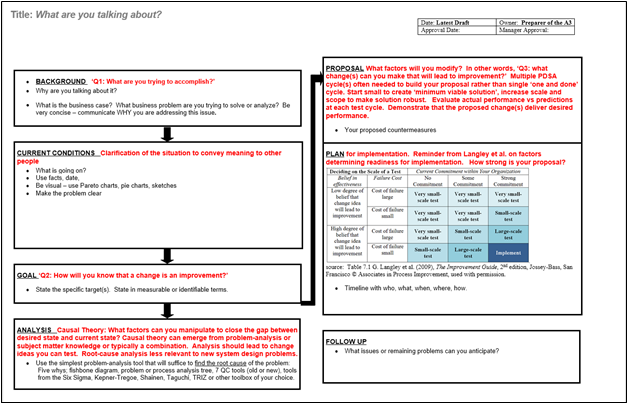

A3 problem-solving guides a user through several steps. With a name derived from the size of paper originally used at Toyota, the A3 user first describes the problem—a gap between desired performance and current performance. Next, the user figures out why there is a gap, then proposes a solution, and plans the steps to apply the solution. An A3 form, from the Lean Enterprise Institute here, shows typical steps.

The A3 form is designed to communicate a problem and solution. In contrast to the schematic Model for Improvement, the A3 form includes project elements that users of Model for Improvement would typically summarize in a charter document: the owner of the problem, the business context, and expectation that a relevant manager will review the A3 work.

Finally, the process of drafting and using an A3 represents an authorization to take action to improve the organization’s performance:

“Just as kanban cards give authorization to either make (production instruction kanban) or move (withdrawal kanban), pull-based authority through the A3 process provides individuals with the authority they need, when they need it….” (Managing to Learn, p. 110)

The small boxes at the top of the A3 form for manager approval and approval date are not window-dressing—by Shook’s description, manager approval of the problem description and solution means the A3 owner is authorized to put the solution into practice.

Combining Model for Improvement Thinking with an A3 Form

The A3 form may suggest that A3-problem solving is linear and straightforward, contrary to the advice and coaching of experts like Shook. The A3 owner may need multiple test cycles before she can identify a solution.

A bit of confusion may arise for those learning to use the A3: the Plan step in the form refers to a plan for implementation, not just a plan for an initial test of an idea. Successful implementation typically requires strong commitment from your organization, high degree of belief that the change idea or solution will lead to improvement, and bounded cost of failure.

A3’s may also be used for planning or developing a new system. In this case, analysis of past performance may have no clear boundaries unless you have the discipline to focus on a design that addresses system purposes. Thus, ‘root-cause’ analysis is not useful advice in planning and design problems. On the other hand, development of a new system design still requires a causal theory. To accommodate both operations and planning/design problems, I interpret Analysis to mean ‘Develop a causal theory’.

It is easy to find a home for the Model for Improvement’s three questions and to emphasize PDSA testing in the development of a proposed solution. Here’s my amended A3 instructions to integrate Model for Improvement Thinking.

These notes make me more ready to build on the Model for Improvement when I work with colleagues who embrace A3 problem-solving. An editable version of the annotated A3 document is available here.

A note on Check and Study

The traditional Japanese expression of the Deming Cycle is ‘Plan-Do-Check-Act’, for example K. Ishikawa (1990), Introduction to Quality Control, 3A Corporation: Tokyo, p. 38. Ron Moen and Cliff Norman in their 2010 Quality Progress article “Circling Back” describe relevant history, including Deming’s emphasis on Study as the proper label for the third step in the four step cycle. Shook agrees with Deming’s interpretation; he advises users to interpret the Check step as “study and reflect.” (Managing to Learn p. 96).