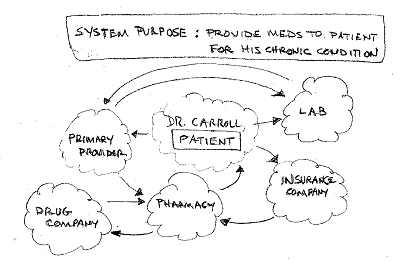

System problems: refilling prescriptions for a chronic condition

Dr Aaron Carroll in his 21 September 2015 column in The New York Times describes a sequence of recurring challenges getting refills for medicine to treat his ulcerative colitis.

As Dr Carroll succinctly sums up the story:

“There is no bad guy here. I love the drug company that created this medication. The price is more than reasonable. I love the doctor who prescribed it to me. My insurance company has never refused to cover my care, and has always been honest with me. The laboratory personnel are professional and competent. It’s the system — the way all these things work, or fail to work, together — that’s the issue.”

Dr Carroll has described a systems problem--remember the simple definition of systems I’ve borrowed from my colleagues at API, in The Improvement Guide (p. 37)?

“A system is an interdependent group of items, people, or processes with a common purpose….In a system, not only the parts but the relationships among the parts become opportunities for improvement.”

In Dr Carroll’s example, the system purpose is not known by the people other than Dr Carroll. It's not surprising that the relationships among the parts don't function to achieve Dr Carroll's purpose. Getting the parts to work together, toward a common purpose, is a planning and design problem. The Model for Improvement stands ready to guide the work, once we get the right people talking to one another.

Of course, it takes the right people to decide to tackle systems problems, a thorny challenge—people with sufficient knowledge and interest to make things better have to agree to work together. No individual or team appears to have responsibility for the entire system in Dr Carroll’s problem; immediate interests of people running the component parts don’t yet align with a common purpose.

It surely helps to have relationships with people who represent different chunks of the system, to foster an initial exchange of views and to gauge interest in tackling the problem together. I’m involved in a couple of system projects right now where there is no “boss” and we’re feeling our way forward, using our personal connections. In systems with broken relationships, it looks like somebody has to make the first call, to reach out to people in other parts of the system. So the next step after recognizing the problem requires developing connections with people--to knock on a door, make a phone call or buy somebody a cup of coffee and just start talking with a system sketch in hand.